Top image courtesy of Orlando McGill.

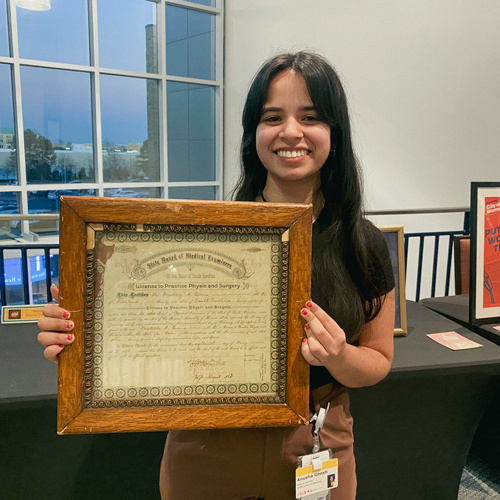

It’s the fall semester of 2021, and Anusha Ghosh, a first-year pre-med student, is conducting research. After ensuring that her workspace is tidy, she completes the final step of her preparations: pulling on a pair of gloves. Then she reaches, not for a beaker, microscope or scalpel, but for a collection of records from the Good Samaritan-Waverly Hospital.

For Ghosh, the archives of the Caroliniana Library hold as many answers to public health’s largest issues as any research lab. The Stamps scholar, who is now a first-year medical student at the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Columbia, understands the importance of learning from former public health trailblazers — especially those from underrepresented backgrounds.

In the same way that a doctor would take a patient’s medical history to learn more about how to treat them, Ghosh conducted diligent historical research to discover how Dr. Matilda Evans (1872 – 1935) galvanized the Waverly community in Columbia, South Carolina, into making public health improvements. What she learned and wrote about in her Honors thesis became the foundation of South Carolina’s Matilda Evans: A Medical Pioneer, a forthcoming book by Walter B. Curry, Jr., Ghosh and Beverly Aiken Muhammad.

“When people don’t learn local history, especially health care workers, then the initiatives, the progress that they made can get lost,” says Ghosh.

A commitment to community

Ghosh didn’t set out to conduct historical research; originally, she had her heart set on being a paramedic. But she has always been passionate about public health and providing care to populations that are often overlooked.

“The more I got connected with the medical field, the more I realized how much disparity prevailed,” she says, “and how much of that disparity needed to be resolved by physicians, the people who were the leaders in medicine and medical research.”

It didn’t take long for Ghosh, who is from Greenville, South Carolina, to engage with the USC and Columbia communities. As an undergraduate, the BARSC-MD student volunteered with Pathways to Healing, a local organization committed to supporting sexual assault survivors and ending sexual violence. She was also a regular volunteer at the Free Medical Clinic in Columbia, and now, as a medical student, she is eager to be involved in street medicine, which provides medical treatment literally on city streets.

“A main driving factor and something that hasn’t really changed is my desire to help people where they are and to resolve the disparity that persists in a lot of areas of medicine,” says Ghosh.

She credits many of her Honors classes, such as the Homelessness in South Carolina course, for providing an academic foundation for investigating some of public health’s most pressing challenges. But it was one class in particular, The Development of Modern Medicine: 1800 to Present, taught by Dr. Burke Dial, that inspired her to explore medical history.

“Every single day after class, I would go to his office and talk to him for at least an hour about what we learned in the class. I was so fascinated by how much history and how many minds came together to make the field of healthcare the way it is today.”

Discovering Dr. Evans

It was Dr. Dial who introduced Ghosh to Dr. Matilda Evans and the Good Samaritan-Waverly Hospital. As Ghosh would discover, “Good Sam” was a prominent hospital serving the Black community in Columbia, operating from 1952 – 1973, at the height of segregation.

“I wrote my final paper on the Good Samaritan-Waverly Hospital, and I realized how much history was missing in that aspect,” says Ghosh. “I realized how unsatisfied I was with only writing 12 pages about this hospital that did so much for the community and had such a special story behind it.”

As Ghosh discovered through her research, the hospital was almost entirely funded by the predominantly Black Waverly community. Doctors lived, worked and worshiped alongside their patients, creating a powerful sense of community that captivated Ghosh.

“Such a special bond that existed between the patients, such a special line of trust. I feel like that's something that's difficult to find nowadays between physicians and especially minority populations.”

When she told Dr. Dial that her research felt incomplete, he recommended that she conduct independent research on Dr. Evans, the first Black woman certified to practice medicine in South Carolina. Dr. Evans was a forerunner of Good Sam, with many of her initiatives setting public health precedents that the hospital would embody. This research became the basis for Ghosh’s Honors thesis.

For the next three years, Ghosh combed through primary sources. Bobby Donaldson, the executive director of the Center for Civil Rights History and Research at USC, connected Ghosh with Dr. Evans’ living relatives, Walter Curry and Beverly Aiken Muhammad. She interviewed both, and Curry took her to a Sunday service at the church where Dr. Evans was baptized, Smyrna Baptist in Aiken, South Carolina. Ghosh also developed a relationship with Aiken Muhammad, Dr. Evans’ granddaughter.

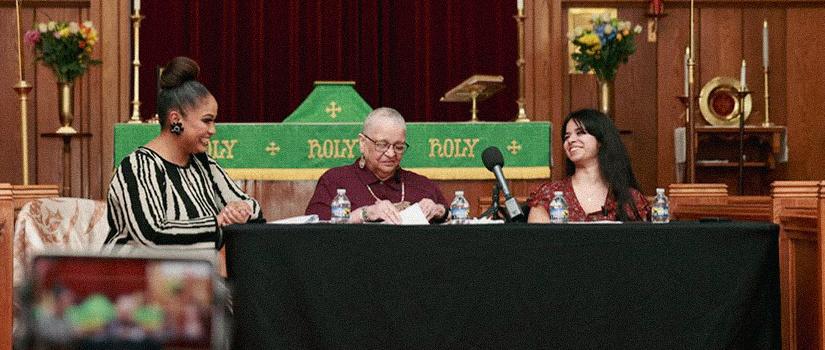

On February 15, 2025, Ghosh and Aiken Muhammad spoke on a panel hosted by St. Luke’s Episcopal Church, which was Dr. Evans’ church when she lived and worked in the Waverly community. Aiken Muhammad mentioned that she first connected with Ghosh while undergoing chemotherapy treatments for cancer.

“She was so bright and brilliant and curious,” Aiken Muhammad recalled during the panel presentation. “People our age love curious people — it’s like water to the soul.” She went on to explain that her conversations with Ghosh about her grandmother buoyed her spirits throughout the chemo treatments: “The more questions she had, the more she brought out in me.”

She and her husband also have a nickname for Ghosh: Dr. Matilda Evans, Jr.

“And I’m like, ‘Oh, my goodness, I cannot be Dr. Evans,’” says Ghosh. “I’m not even half the woman she was.’”

History will make the final determination on that. At present, Ghosh is connecting Dr. Evans’ initiatives to the disparities that she sees in modern healthcare, and she plans to apply some of Dr. Evans’ techniques to address the health challenges that many minority communities still face.

“Healthcare providers are responsible for uplifting the health of community members and patients outside of the clinic,” says Ghosh.

Uplifting a legacy

While presenting her completed thesis at the 2024 Honors Thesis Symposium, Ghosh stressed the importance of learning local history and preserving Dr. Evans’ legacy. She was humbled to learn that her thesis — which is over 100 pages long due to the sheer number of Dr. Evans’ positive impacts on public health — served as the framework for a book about Dr. Evans’ life. Curry supplemented Ghosh’s research with his own, and together with Aiken Muhammad, they wrote South Carolina’s Matilda Evans: A Medical Pioneer.

The book, which will be available on April 8, details Dr. Evans’ life and medical achievements. Some of those include her weekly newsletter, The Negro Health Journal, which she disseminated to Waverly residents; her founding of South Carolina’s Taylor Lane Hospital and Training School for Nurses, the Evans Clinic and the Zion Baptist Church Clinic; vaccinating over 4,000 children in one day at the Evans Clinic; and her state medical certification exam results being superior to her white male counterparts’. Due to Ghosh, Curry and Aiken Muhammad's efforts, Dr. Evans’ legacy can reach a much wider audience.

Ghosh, now in her second semester of medical school, knows that her work in healthcare has only begun. But this project has already proven that she can make incredible contributions to the field — and she encourages other students to embrace their own opportunities to have an impact.

“My Honors thesis changed my life,” says Ghosh. “I definitely think it’s the best thing about the Honors College — being able to be more than a student, to be someone who can contribute to society and your professional field.”